NOTE: For formatting reasons, it is better to view this on a computer screen than a handheld device.

Poet………………………………………………Poems

The Editors……………………………………Introductions

Jan Barry (1)…………………………………..Here We Go Again

Patricia Carragon (2)……………………..Russians

……………………………………………………..Haiku

Patricia Spears Jones (1)………...……...Thinking of Ilya, Odessa and February

………………………………………………………….Thaw(s)

Hanna Komar (1)…………………………….Ukraine I Hear from London

Adele Kenny (1)………………………………Remember This (Ash Wednesday 2022)

Beth Levin……………………………………...My Bubba Put Away Her Rushnyk Blouse

Richard Levine……………………………….At the Center of Everything

Djelloul Marbrook (1)………………………Demurral

Al Ortolani (1)………………………………….Reading William Stafford After the

……………………………………………………………Russians Shell the Nuclear Reactor at

……………………………………………………………Zaporizhzhia

Stephanie Rauschenbusch (1)………….Reversed Worlds

Bertha Rogers (2)…………………………….The Children’s War

..………………………………………………………Winter's War

Liz Rosenberg (1).……………………………Body Speaks to Soul

Michael Simms (2)…………………………..No

..……………………………………………………..Rumor of War 2/24/22

David Vincenti (1)..…………………………..Overture

Gerald Wagoner (1)..………………………..Tide Pool Poem

Joe Weil (1)…..………………………………….Vespers in Blessing of an Old Woman

……………………………………………………….……Shaped like a Potato

Michael Young..……………………………….Planning Retirement as War Begins

The Editors………………………………………Afterword

Artist………………………………………………..Artwork

Eugenia Chun-Bianca Sanchez………..Dreaming Peace

Richard Levine…………………………………Invasion of Ukraine 2022: Poems (cover)

Bertha Rogers………………………………….End Winter’s War this War to End

…………………………………………………………Winter, War

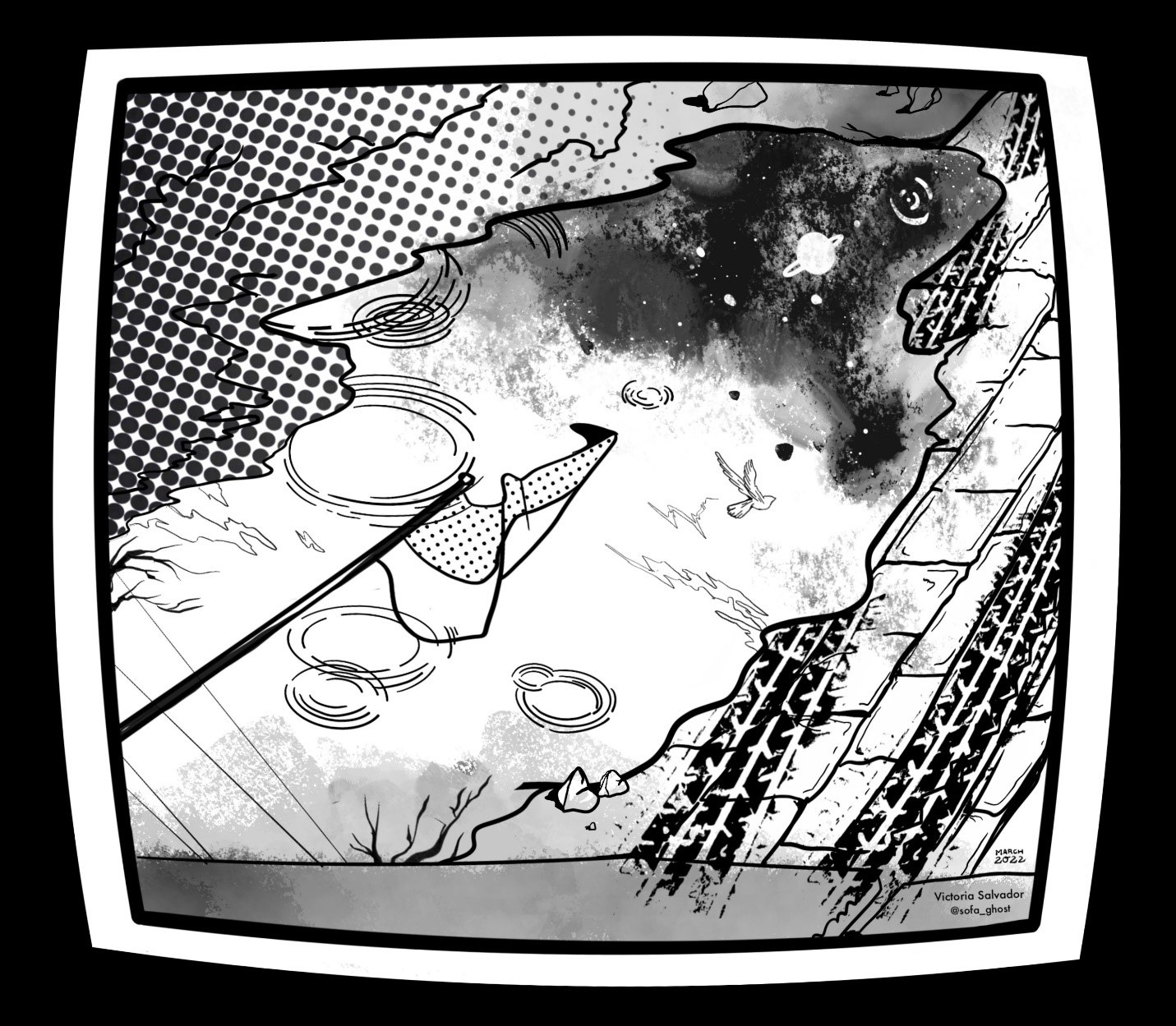

Victoria Salvador……………………………..Reflecting in Real Time

Introductions

“Human beings suffer./They torture one another./They get hurt and get hard./No poem or play or song/can fully right a wrong.” Seamus Heaney.

The poems gathered here were all written since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, on Thursday, February 24, 2022. Even the ones written in a matter-of-fact tone seethe with an underlying sense of shock and emotional recoil.

As I write this introduction, the fighting has raged for 13 days. Everyday the Russian army shows more of its superior equipment, force and numbers. Every morning there is more rubble in more cities, where apartment buildings, hospitals and schools stood in their useful occupations. And in every action the Russians display more savagery and disregard for human life, establishing safe passages for people to leave and then shooting them. And yet it is the muscular bravery and resistance of the Ukrainians, in words and deeds, that suggests the impossible and keeps alive a hope that the rest of the world, as it watches, wants to believe in.

In The Moon is Down, John Steinbeck’s novel about the power of spirit in war, a small mining town in Norway is invaded by the Nazi army. When the Nazi commander boasts at how easy it was to conquer them, the town’s mayor says, “Our people are invaded, but I don’t think they are conquered.”

The townspeople have no army, no militia, few weapons, and yet the Nazi’s never do conquer them. In the book’s final passage, the mayor offers the commander a history lesson we may be seeing unfold in the Ukraine.

“The people do not like to be conquered, sir, and so they will not be. Free men cannot start a war, but once started, they will fight on in defeat. Herd men, followers of a leader, cannot do that, and so it is always the herd men who win the battles and the free men who win the wars.”

In his introduction, my co-editor, Michael T. Young, wonders “… why I or anyone like me would feel a need to write poems in response to other people’s suffering so far from our own relatively peaceful lives.” Maybe it’s because these words want to be part of the struggle of a free people, a struggle we may feel we’re in everyday, even in peace.

“History says, Don’t hope/On this side of the grave …/But then, once in a lifetime/The longed-for tidal wave/Of justice can rise up,/And hope and history rhyme. (Heaney.)

Richard Levine,

March 2022, Brooklyn, NY

I am not in a war-torn country. I am safe in my home with my wife and children. I have never had to flee my house, my city or country, leaving behind the life I had come to love. So, it may be wondered, why I or anyone like me would feel a need to write poems in response to other people’s suffering so far from our own relatively peaceful lives. I would say of humanity what J.F.K. said of freedom: humanity is indivisible and if one person’s life is endangered, all are endangered. I am an ordinary citizen, but I feel the necessity to witness the wound to our common humanity. We may live in another hemisphere or in a country adjacent to Ukraine, but in the privacy of our lives, the ordinary citizen feels helpless and pained as that common humanity is shredded by the dark ambitions of those whose power is such that they can disregard the lives of others. So, the poet articulates that pain, not to magnify darkness but to see through it, to give language to our common need. For language is a key, a shibboleth to escape our isolation into remembrance, into a place where we might find the shared ground that extends a hand or points a way out.

Michael T. Young,

March 2022, Jersey City, NJ

Here We Go Again Jan Barry Here we go again, Back in the saddle again, War in Europe again, Where “Kilroy was here”— 3rd Infantry Division, paratroop combat brigades, B-52 bombers, fighter squadrons On the move to front line positions Facing the bearish threat of yore— Been there before, I grew up training to fight the Russians, Hunkering in school hallways In nuclear war drills— Now a new generation of GIs Is headed into the war zone To face off with the Russian army Rampaging across Ukraine— Flashbacks flash across the TV, Across my brain— Dragging me back in time To the world war where I was born Environmental writer/poet Jan Barry’s books include A Citizen's Guide to Grassroots Campaigns, Life after War & Other Poems, (co-editor) Winning Hearts & Minds: War Poems by Vietnam Veterans. Veteran of Vietnam.

Russians (inspired by Sting) Patricia Carragon A disease lives in a man, hides behind an eastern cross, duct taped his people with sheep-skinned lies. His disease thrives on the past— a grown man plays colonizer games with no questions asked. His disease continues to attack where resilient sunflowers grow taller, stronger, faster than fire from bombs and guns, faster inside those who’ve had enough. Iron curtains have deep-rooted cracks, can’t keep the truth or sunflowers out. Yes, Russians do love their children— most say nyet to Putin’s sick game. I am Ukrainian, I am also Russian— two nations planted my DNA tree. Resistance and biology have no borders, and from these hands, my sunflowers grow.

Haiku Patricia Carragon bombs cannot destroy the tiniest sunflower blue Ukrainian sky Patricia Carragon’s latest books are Meowku (Poets Wear Prada, 2019) and Angel Fire, (Alien Buddha Press, 2020). Patricia hosts Brownstone Poets and is the editor-in-chief of its annual anthology.

Thinking of Ilya, Odessa and February Thaw(s) Patricia Spears Jones Temperature balmy then dropped- -a ball of wind Blasting buildings and trees. Cats hide beneath cars And birds are quiet. But not the sirens that start calling early morning Along with the chiming bells of Our Lady of-- This is where the mischief maker enters, stage left straggling Words --Perpetua, Sorrow, Victory, Toil, Ardor and Amor. Russians are starting a war in Ukraine meant to show They can start a war adding more terror to the terroir. Putin brings out poor puns and this sense of the inevitability Of un mocked imperialistic ambition, how power cleaves to men with little time for morality, in their wake ruin and stench from an obsession with plunder. They stand tall in their decisions monuments untouched by pigeon shit. These dull words: war, imperialism, power, Putin pumped up This thump thump thump of old ideas done the old way & yet new Cyber-attack, then explosions. Denial and Demand. It’s the game gamers dream –but there’s this caveat There are no avatars Few faux numbers, Or glum predictions Inside a console. There are men and women and their war machines and desire for omnipotence. And the night skies light with bombs And the daylight will show what is standing And many will blame our president for what he could not do, Stop a war, Patricia Spears Jones is an African American poet, and playwright. She’s winner of 2017 Jackson Poetry Prize, author of A Lucent Fire, and The Beloved Community forthcoming from Copper Canyon.

Remember This (Ash Wednesday 2022) Adele Kenny The lilac is still bare, but a robin (the first this year) stands where tulips will be. Snowdrops bloom around the fountain— a kind of sparkling. Sparrows and squirrels come to the feeding table, wild yet peaceful. After two years of Covid, the news now is mostly about Putin. What started as a lie became the truth—we watch Ukraine as it’s leveled into rubble and ash. We watch death happen. Russian forces have even bombed the Holocaust Memorial at Babi Yar, where Nazis slaughtered thousands of Jews in 1941. History repeats and repeats; little, it seems, will change hearts or unbend hatred and greed. Time and everything lost are ways of falling. Here, a mockingbird sings another bird’s song, and I tell myself our human spirit is a springtime that will go on rising until the sky turns and takes us with it. I tell myself we are bits of sun that glint like unexpected crystals on white stone. The walk from one side of my fence to the other is short. I pick up pine cones that have fallen and bring them inside (like all things that must be kept), by that I mean remember this‚ it’s important. Adele Kenny is author of 25 books (poetry and nonfiction), poetry editor of Tiferet Journal (since 2006), and founding director of the Carriage House Poetry Series (1998-present).

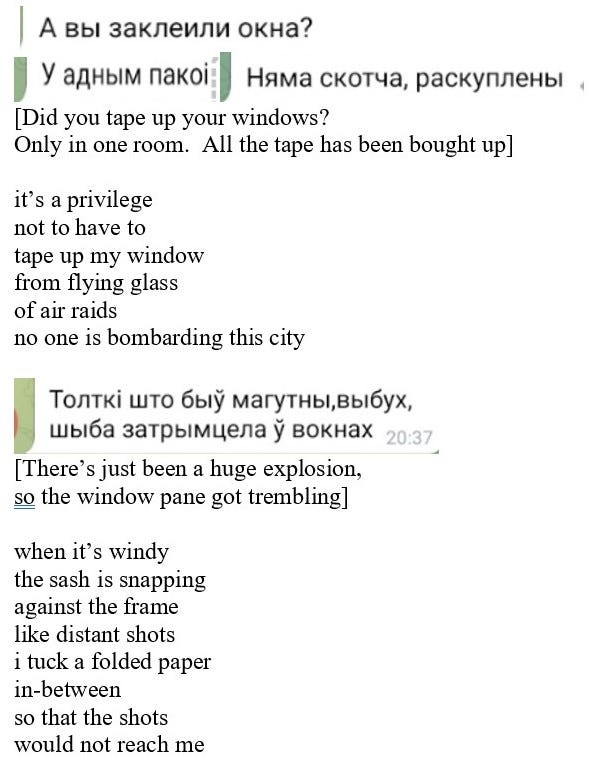

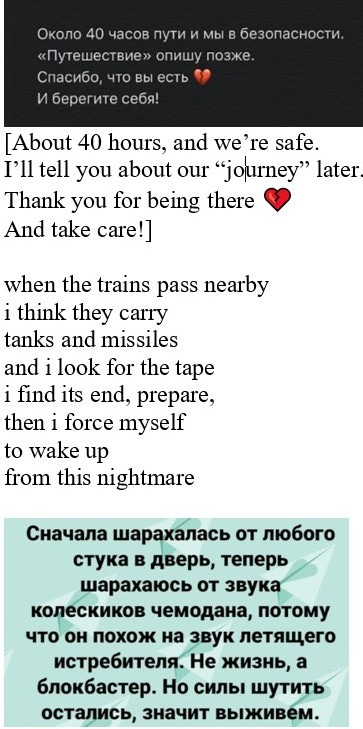

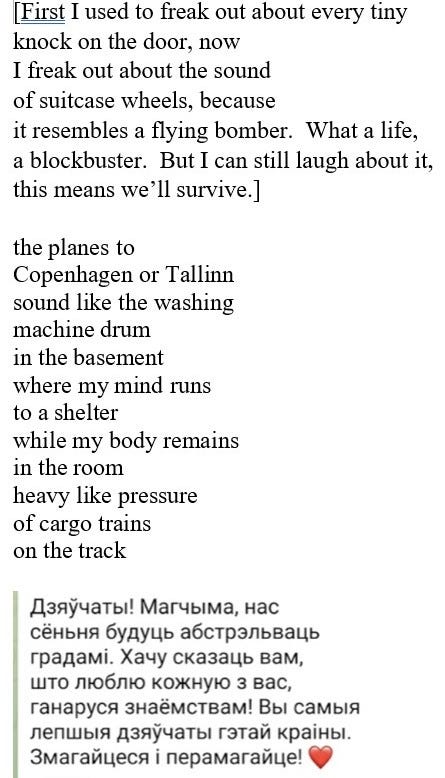

Ukraine I Hear from London

Hanna Komar

This is a documentary poem in which i used clips from conversations with friends and their publications on social media.

Hanna Komar is a Belarusian poet and translator currently doing an MA in Creative Writing at the University of Westminster, London. She has many friends who are staying in bombarded Ukraine.

My Bubba Put Away Her Rushnyk Blouse Beth Levin My Bubba put away her Rushnyk blouse when she came over cut her hair into a bob struggled to learn English sending my mother to the butcher for stew meat and tongue I remember her in elegant coat and bag I remember the Renoir print on the wall *** Her kitchen in the house on Diamond Street sang a Kyiv folk tune Borscht asimmer on the white stove honey babka on a tiered copper plate hard-boiled eggs *** After my grandfather died she would sit in the sunny front room to watch TV When I stopped in for lunch she told me little about her life before I always knew it had been a great love story a heroic saga (Poltava Region, Ukraine, 1926) Beth Levin is an internationally celebrated pianist and bold interpreter of classical works. The New Yorker called her playing "revelatory." Her poems set to music premiered March 20th in NYC.

At the Center of Everything Richard Levine I am near tears as I read of a Russian mother reading a letter from her son. He is eighteen, in the army, in a convoy heading for Kiev. His first letter said they’d be welcomed, cheered. This letter speaks of treachery he’s seen and what they’ve been ordered to do to the men, women and children of Kiev. She fears it will ruin him. I know she’s right; there are places in Vietnam that even now close my heart, places where I discovered that you can live on after your heart’s stopped. She knows he can’t refuse the orders or he’ll be shot. Or, if there is mercy, he’ll be jailed, like Galileo, who also saw that our light was not at the center of everything. Richard Levine, a retired NYC teacher and Vietnam veteran, is author of seven books. Now in Contest is forthcoming from Fernwood Press. He is an Advisory Editor of BigCityLit.com. website: richardlevine107.com

Demurral Djelloul Marbrook Stardust to no purpose or purpose so grand we imagine death to define it, stardust hurtling towards Andromeda, stardust of a universe expanding, demanding minds to encompass it, and we invent tragedies, contrive low purposes to filter grandeur, tinker majesty too much to bear. Invade Ukraine, sell arms, wave flags, tout genealogies, all to deny we’re reigns of ancient light, rains of purpose, positioning, event, and when we ask what’s next we demur, put off the moment, and this demurral’s dance we call literature, meaning, this demeaning put-on and put-off, this shedding, shading that’s hardly dandruff of the gods. Stardust to no purpose we pronounce as news, supremacist claptrap, stonehenge of artifacts to no avail, fleeing here, us particles of the moment, us ecstasies, us epiphanies shivering in each other’s bones. This rattling hurtle is too much for anyone to bear, so surely we must be one inside the pit, the tooth and blast of oneness, wondrous if only to put our identities down, to let them sift between our naked toes with the o’s of our divine decision not to be such trouble to ourselves as family, category, belief, staring the moment down, paying more for gas, looking bleak, and flirting with the harrowing idea we might be all we need, and the bridge from alpha to omega built of forgiveness, patents held in the silliness of our hearts. Djelloul Marbrook first collection of poetry, Far From Algiers, won the 2007 Stan and Tom Wick Prize. He’s published 20 books of poetry and fiction, most recently, Lying Like Presidents, New and Selected Poems, Leaky Boot Press, UK.

Reading William Stafford After the Russians Shell the Nuclear Reactor at Zaporizhzhia Al Ortolani There’s a place in the woods where we walk, dog ahead, nosing out voles, the scent of rabbits, whatever has left itself behind from the night. I follow, slower than I once did, but still able with my one good eye to see that the trees are junipers, blue berries lit with tomorrow, more vivid than the evergreen’s fan of needles, the spray of stored sunlight. In the deep branches an invisible bird breaks into trills, songs to warn others of our passing. We have our moment here today, and tomorrow, well maybe, we are just a trail, what we’ve left behind from our daylight, boot prints in the mud, paw prints circling back upon themselves, a good nose, an eye on hope, following a trail through the woods without war, without bombs, without fires which tomorrow’s children must fight. After 43 years of teaching English in public schools, Al Ortolani lives a life without bells and fire drills in the Kansas City area.

Reversed Worlds Stephanie Rauschenbusch I walk in puddle after puddle surrounded by alternating rain and snow. Each puddle holds a world of tree branches and sky. How unspeakable it is that people in Mariupol must drink water from puddles in the Czar’s war. Stephanie Rauschenbusch, a poet, writes reviews for American Book Review, paints in oil and watercolor, and has given time to the Women’s Caucus for Art and the Brooklyn Watercolor Society.

Victoria Salvador created “Reflecting in Real Time,“ after reading “Demurral” (Djelloul Marbrook) and “Reversed Worlds” (Stephanie Rauschenbusch).

Sketched, drawn, and executed in its entirety, digitally, on Procreate.

Victoria Salvador is an artist, musician, and sculptor from Central NJ. BFA in Illustration, Parsons the New School for Design. Favorites: Optical illusions & puzzles. View her work on Instagram: @sofa_ghost

The Children’s War

Bertha Rogers

It was the children. They wanted

nothing but to be held

by their mommy and daddy,

but that want was less than war.

Although their want wanted quiet,

wanted arms about their shoulders,

it was too small to succeed.

What succeeded was war.

War’s bright fire always wins

because it wants more than

arms about spare shoulders.

So it was the children who lost;

their want was not tall enough

or wide enough to bury the fire

spit from the mouths of guns. Winter's War Bertha Rogers This is the one, the hindmost goodbye, the end-of-world, unholiest one. These are the funeral-plumes rising— Beelzebub red, hot, fermented black. These are the old ladies, the children. They stumble and stagger over what used to be windows and walls, babushkas slipping from their heads, mittens escaping frozen fingers. They are wild, they lift their arms, they fall and cut their legs on porcelain plates and silver forks that ride the sea of human debris. Hungry, they weep, they thirst, they howl for bread; their bellies ache. There is no warm place, never, no more. Bertha Rogers’ poems have been published in journals and anthologies and in several collections, including Wild, Again (Salmon Poetry, Ireland, 2019)

Bertha Rogers created this illustration as a companion piece to her poem “Winter’s War.”

Pastel, Watercolor and India ink on Paperboard

12" x 11"

Body Speaks to Soul Liz Rosenberg In the wintriness of winter, oh my Soul, how can we survive the cleaving— I had not been thinking about Ukraine, I had not been thinking of the torn and newly killed, nor of the killers who laid down their arms and on their tongueless boots fled to the Crimean forest. I cannot always be thinking of my sister in her narrow nursing bed or I would go mad, run myself through the snow like a bladed plow. Then can I help? Everything is flat and ghostly-pale in the absence of sisterly pity for all this … This suffering world sticks like a bone in the throat that would prefer singing to itself. Liz Rosenberg writes poetry, novels, and books for young readers. Her most recent is a biography of Louisa May Alcott, from Candlewick Press. She teaches at SUNY Binghamton, NY.

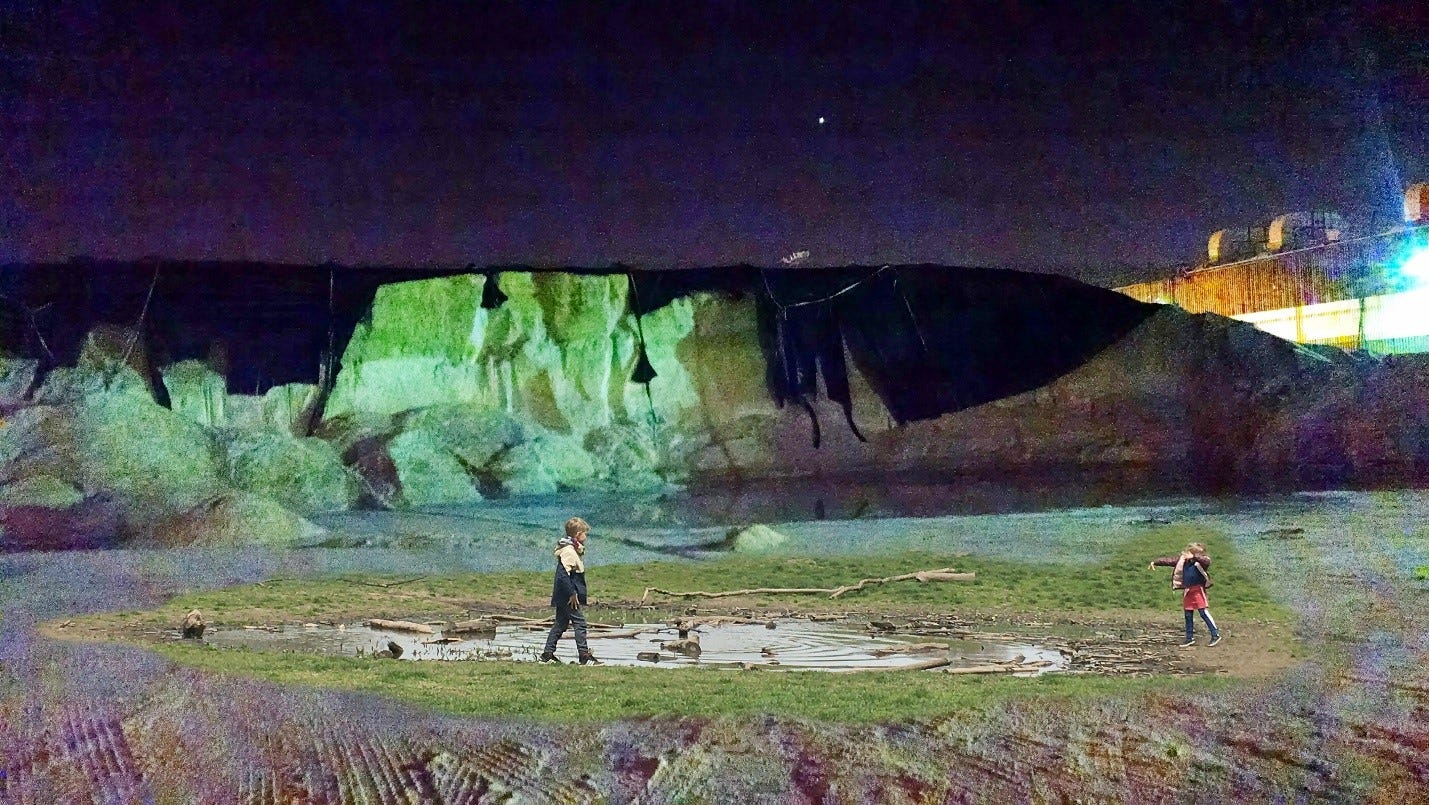

This photo-collage, “Crystalline Kids,” is from a series “Dreaming Peace,”

by Eugenia Chun and Bianca Sanchez

Eugenia Chun is a practicing artist who works as an Academic Advisor at SVA and smiles through life in NYC. Find her blog and recent work at https://eurajean.wixsite.com/blog.

Bianca Sanchez is a visual artist living, practicing, and teaching mindful art to kids in Brooklyn, NY.

No Michael Simms for Vladimir Putin No is the place to go when yes has been all used up. No is the waking from the darkness of sleep, returning to a blessed country from a bad dream. No is the rhythm of assertion, the hammer of refusal, the long pause before acceptance of the coming battle. No is the full stop, coming to sense after a long foolish year. No is standing up to tyranny. No is the extinguished fire, the frame around the picture, the inviolable border. It is the slapped hand, the hard stare, the nostrils flared like a bull’s. No is the long syllable growing to a roar, the single syllable stomping the ridiculous, the insulting, the oppression of the bully and the evil of the rapist. No is not nothing. When everything has been taken from you, no is all you have left. No is an affirmation of the right to hold out, the refusal to let go. No go, hell no, you go, we stay, we want what we want and we want it now. No is the pile of dust swept out, floors scrubbed raw, skin blistering with the sun of yes-boss said too long. No is the shade on a summer’s day, the rest of the tired hero. No is the pause, the re-set, the do-over, the change of direction. No is the new direction, a destination that is not your yes on your terms. No is not maybe. No means not ever, no way, not this way, no sirree, bub, hit the road Vlad, shut your pie-hole, Donny.

Rumor of War: February 24, 2022 Michael Simms As you read Die Zeit, you’re translating for me the story of the war that’s begun not far from Siegen, and I remember the spires of your small city in Westphalia, the old-book smell of Klaus Feiertag’s shop on Kampenstrasse, the few gabled half-timbered buildings that survived the bombings, the intricate iron door-strappings and fittings, the ornate hinges and handles you love to photograph, the fishtail fans, the Celtic mazes, the orbs and eyes and swords of iron, details of roof windows, sills and sashes, beams and gutters, soffits and fascia, swirling patterns carved into slate walls, every element crafted with attention, the squat chimney pots like gnomes looking out over the rooftops to the far mountains, the towers on the hill guarding the city destroyed and rebuilt repeatedly through the ages. I imagine you as a teenage girl loving this city climbing the long-cobbled road up Siegberg hill, the old palace of Oberes Schloss converted to a museum. Although you hurry past the painting by Rubens, your townsman, The Rape of the Daughters of Leucippus depicting muscled Castor and Pollux gripping two naked women while a black-winged putto looks on, you stop to read the 3,000-year history of the men in your family tunneling through red rock of iron ore, dust clogging their lungs, killing them slowly. And you think of the women dying of childbirth, dying of endless work, of grief, of rape and hunger. You hurry across the hard floor of greywacke stones set in a herringbone pattern and outside, climb a medieval bastion to look down at the city spread out below and the Hüttental Valley beyond. You love this park in the spring when 60,000 tulips are in bloom and in summer the outdoor concerts of oompah music. Dicke Turm means Fat Tower, but tourists sometimes call it Fat Dick, a cruel name for a handsome edifice with a carillon that chimes every two hours. Even older and taller in the medieval core of the city stands the Nikolaikirche, a red and white church tower topped by the Krönchen, a gilded crown, the shining symbol for medieval Siegen. And you think of this beautiful city, your city, your father’s city attacked by British bombers in 1944. Your father, just a boy, hid beneath the stairs as the house came down around him. After the bombs stopped falling, people emerged from basements and tunnels where they’d been hiding to look for food and fresh water. Every building was a smoking ruin. Even the church tower was half-demolished. You’ve told me of The Aktives Museum where Siegen’s one synagogue burned down during Kristallnacht. And you’ve told me of Walter Krämer, hero of the Westphalia resistance, prisoner at Buchenwald who taught himself medicine to save his fellow inmates. Blessed are the essential workers, as we say in our own dark days. The zoo nearby has white-cheeked gibbons and laughing kookaburras and children can make friends with goats and donkeys. Here you eat schnitzel and roasted potatoes with a tall glass of Krombacher brewed nearby. You walk the cobbled streets of this city founded before the Romans came, before the Franks, the Burgundians, the hundreds of chieftains who fought for control of farms and mines, rivers and forests providing meager work for your family. Your father drove a truck for forty years through the winding rutted roads delivering groceries to villages where people have lived for a hundred generations of rain and snow. The church registry lists a thousand years of your ancestors and beside every man’s name his occupation as miner or farmhand. Your grandmother cooked for the mine owner’s family, and your grandfather’s bookstore was raided when he refused to display Nazi propaganda. Too old to fight, he was sent to villages in the low country and given a shovel to bury rotting corpses. When he found the hand of a child beside the road, he threw the shovel in the bushes and walked home. Captured by the Americans, he spent six months as a POW. He said it wasn’t bad, at least they fed him. You remember his kindness to children, how you learned to read in the nook beneath his desk, but also, how easily he broke the necks of the caged rabbits and how you ran from the dinner table, hid in a closet and wept for them. The ruins of war lay across the city like a shadow. The boy hid beneath the stairs as the house fell around him. I’ll say it again and say it differently because the horror of war must never be forgotten. The boy hid beneath the stairs when the Good Guys came to kill him. You were told not to wander through empty lots of charred bricks, broken blocks, girders sticking out of the ground like bones because bombs lay forgotten beneath the soil. You were warned not to talk to the soldiers who leaned against street lamps watching you walk by, as soldiers of other wars had watched your mother, your grandmother, her mother back to a time when men charged each other with bronze spears and drank mead from the skulls of their enemies. Now tanks are rolling down the streets of your fear as we sit over coffee in our comfortable house far from war in a country sliding toward war and our leaders speak of protecting democracy but never speak of killing children. Your voice carries a hint of your first language like baggage from a past your family has survived. You often say We are the ones descended from survivors. We will survive as will our children. Your brothers and their wives in the old country are safe now, but in your blood is the ancient fear like the winter sun that shines on the broken stalks of our garden, the same sun that shines on the frozen fields of war far away but growing closer. . for Eva Author Note: This is a first draft I wrote on the morning of Thursday, February 24, 2022, after my wife Eva and I learned that the Russians had invaded Ukraine. For Eva, who is German with family and friends living in Westphalia, the news was difficult to bear, recalling the stories she’d heard as a child about the bombing of her hometown of Siegen during the war and the hardships her family suffered in those years, including the leveling of Siegen on December 16, 1944, by the British. Siegen has a rich architectural history with roots that go back to the Bronze Age, and Eva grew up watching the city being rebuilt. The idea that Europe would again be at the edge of self-destruction is horrifying. Michael Simms is the founder and editor of Vox Populi. His most recent collections of poetry are American Ash and Nightjar (Ragged Sky, 2020, 2021).

Overture David Vincenti Here, across the world, the only fires burn in the eyes of madmen who see opportunity in every misery. Explosions can be silenced by remote control, and follow not sirens but content warnings. We watch because we cannot look away, cannot forgive ourselves for feeling far removed and blessed. I search for things we have in common, pull harder on the unblemished bellows of my inadequate accordion. My daughter stops to listen, bathed in polyharmonies. We are learning something here. Next, we will dance. David Vincenti’s poems have appeared in numerous journals and the anthologies A Constellation of Kisses and Rabbit Ears: TV Poems. His work has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. www.davidvincenti.com

Tide Pool

Gerald Wagoner

This is the poem I do not want to write.

This is the poem I try not to think about.

This is the poem I have been avoiding.

In this poem I will not write about

the Oregon Coast, sea anemones, or

hermit crabs, snails, chitons, and kelp.

Never about the slow doom of tide pools,

simmered in a heat plume. No. This is

the war poem that I cannot bear to write.

Gerald Wagoner was raised in Eastern Oregon and Northern Montana under the doctrine of benign neglect. He became a sculptor, an art & English teacher, and now writes poems. gwagoner@gmail.comVespers in Blessing of an Old Woman Shaped like a Potato Joe Weil In the news, they show me a bombed-out children's hospital and Salma Hayek's still sinewy legs. I close my eyes, open them, click the changer: old ladies built like harvested potatoes carry their grandchildren over the border. My sense of God is all wool and lumpy sweaters, muddy fields as if a war must always suck at people's shoes, pull them down into the earth where they can sprout up again in thirty years to repeat the process: grandmother, child, border of mud and snow, bombs landing not far from where the war correspondent stands. I keep waiting for a grandmother to kick one of the news people in the shins, smash his camera, tell him help her carry the life she has forced into a bag. I post about Our Lady. No one listens. The old women in the dark of a bomb shelter pray their rosaries. Who believes they will be a solution to anything? Just the powerless used for daily photo ops. I remember St Vladimir's Onion dome, on Grier Avenue in Elizabeth, New Jersey: twenty Ukrainian women calmly preparing the perogy down in the church's basement. Potato, sauerkraut, raisins, the edges folded with pride. Their voices, jokes, incomprehensible to me, as I took my mother's order—a neat box, tied with string, put it on my bike, and rode home where the perogy would be boiled, fried in butter, with onions. A feast! Old hands provided food not cluster bombs. I turn off the news. Stand outside where a thaw has made everything mud and remnants of snow. I believe twenty old women keep the world from absolute destruction. The little girl in her arms: doll, dirty, coat, dirty and her grandmother setting her down so gently—a feather in the midst of a world on fire. Slowly, the angels, the invisible angels of peace kneel while the men in suits bluster on, while the people of consequence offer their expertise, while a commercial for dog food begins. The woman takes her beads, and blesses herself in the Ukrainian Catholic way, kissing the body of Christ. She begins to pray. Joe Weil is a professor, piano player, and poet who used to be a tool grinder. His latest book is The Backwards Year, published by NYQ books in 2020.

Planning Retirement as War Begins Michael T. Young I weighed stocks and bonds against time, plotting where the clock hands will fall between now and the last day in the office. I looked over advisory sites, asking me how much risk I’m comfortable with. Then news came: cities all over Ukraine hammered by artillery, people fleeing in cars, on foot, images online of shelled buildings, smoking rubble, sirens sounding over the domes. How much risk am I comfortable with? My house still stands, my children play in the park across the street. But even when I was young, played bingo with the family, I’d quit as soon as I won, fearing I’d lose what little I had. I’ve learned that I can hold on until I choke the life out of what’s given because I don’t trust the world’s promises. Too often, they end on the wrong side of barbed wire fences. An anchor on Russian state tv says, “You paid with your blood for these eight years of torment and anticipation.” Do we believe what we believe just because we invested so much time into it? Will taking stock now guarantee a future eight years from now? The bonds that hold us are not liquid, not flowing, and refugees mass at the borders struggling to get their tongue around a new name for home. Michael T. Young’s third book, The Infinite Doctrine of Water, was longlisted for the Julie Suk Award. He received a fellowship from the New Jersey State Council on the Arts. www.michaeltyoung.com

Afterword

A friend asked, what good will writing poems do? What the question implies is true: None of the poems in this forum can stop this civilian-targeted war. But it is equally true that none of them will ever pierce anyone’s flesh, like bullets or shrapnel. And any one of them may enter and lodge in a heart with a lasting message of peace.

We believe that language matters, that literature matters and expresses our most closely held ideals, like self-governing and peace. Opinions about this may vary, of course, but what is indisputable is that providing humanitarian relief to those souls caught in warzones is expensive. By humanitarian relief we mean bare essentials – food, water, medicine, clothing, shelter.

Please consider looking for a way to contribute to a Ukrainian humanitarian relief fund. There are many to be found sponsored by government agencies, non-profit and private organizations, news outlets, religious and community centers, both local and national. The choice is yours and the good news is that there are many. Alas, there are also many less well publicized wars and the people in them no less in need.

Another or additional way to contribute is to call and/or write legislators with messages of peace, join a march, or read or send a poem. Good uses of language, all.

We hope you found favor and perhaps some solace in this forum, Invasion of Ukraine 2022: Poems, but until poems can feed and slake the thirst for peace we all feel, especially for those caught in the crosshairs of war, please consider contributing to a humanitarian relief fund and speaking out. Language matters.

Peace,

Richard Levine,

Michael T. Young,

Co-editors Invasion of Ukraine 2022: Poems

These are wonderful. Bertha's poem, Winter's War, floors me.

Wouldn't it be marvelous if we could have poems from Russia as well as Ukraine? In a saner, more contemplative world we would see poets as frontline observers, people who provide historicity, perspective, underlying and overarching facets. people whose testimony is so much more than a recital of events. We don't remember what newspapers had to say about three royal fools who caused World War I's carnage unless we delve into decaying archives, but what Sassoon and Owen, Ford and Brooke said is part of our literary DNA. We remember Yeats' Irish airman foreseeing his death in the skies over England. A more insightful and responsible media establishment would be telling us what the poets are saying instead of spoon-feeding us political blarney. Who doesn't remember Picasso's Guernica more vividly than than the breathless reports off so many correspondents?